#history

#books

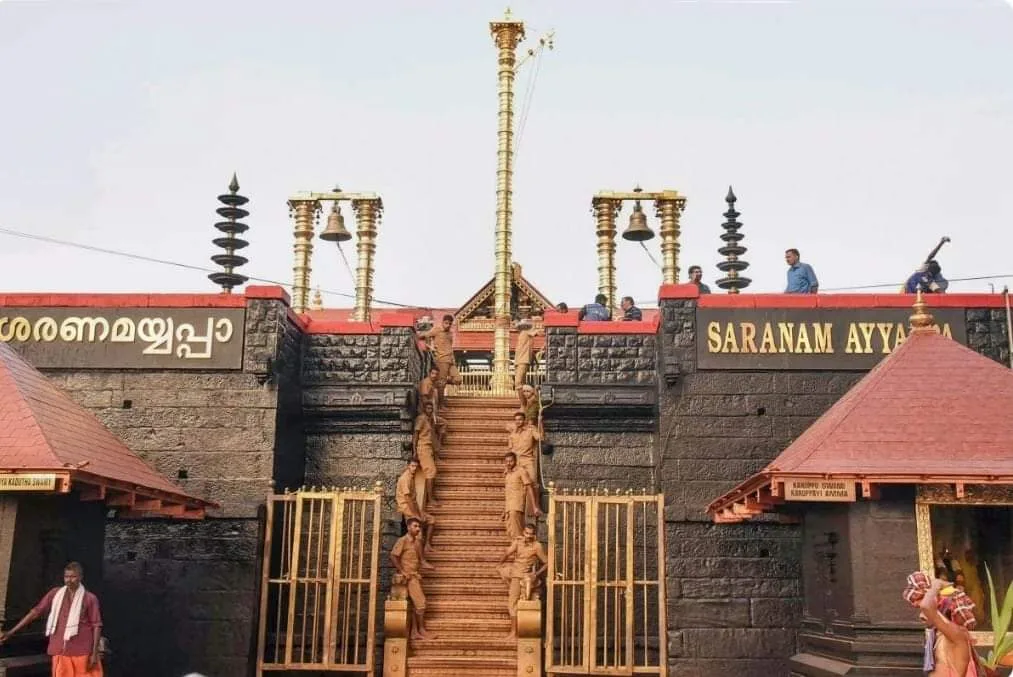

Sabarimala Temple and the Mala Arayan tribals.

One important chapter in the history of the famous Sabarimala Ayyappa Temple in Kerala has deliberately been suppressed by even the historians and the government so as to project the secular temple as an important Hindu temple and pilgrimage centre.

It’s the link of the Mala Arayan tribal community with the Ayyappa temple from the time of its establishment.

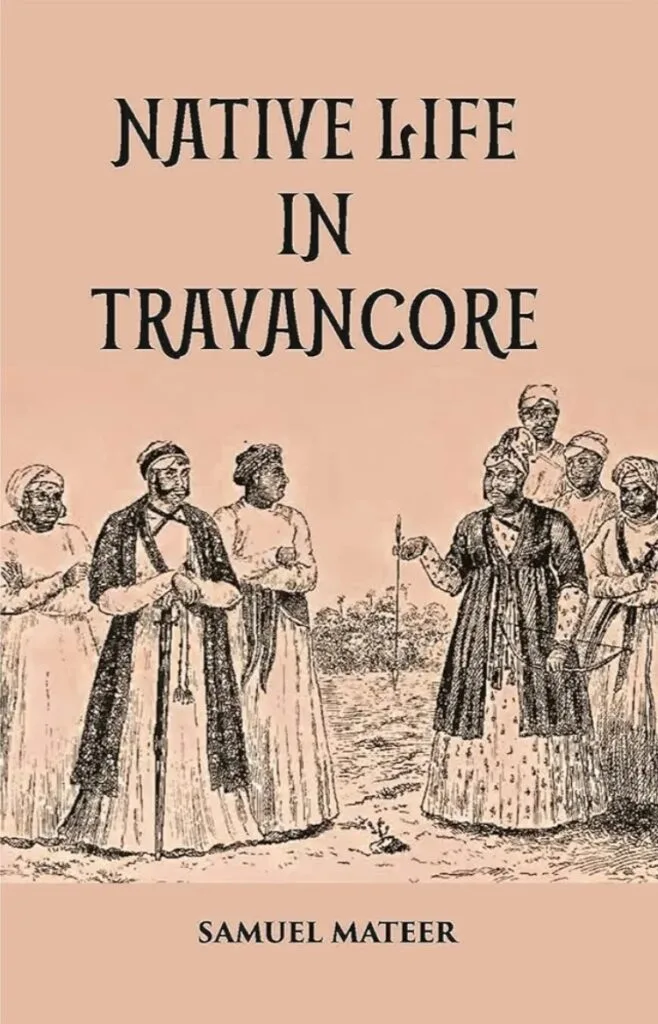

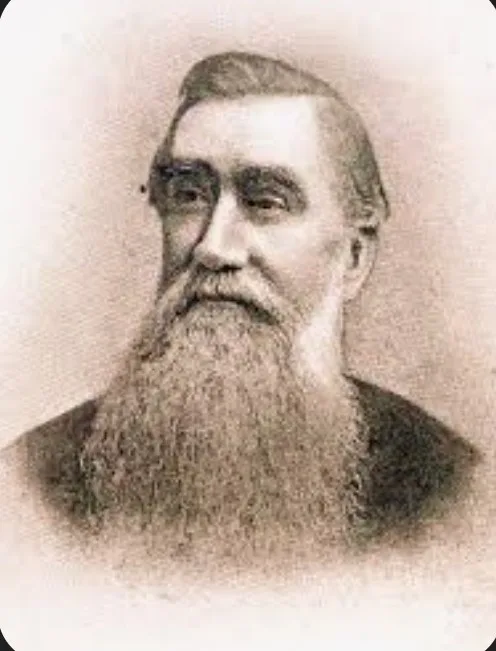

Rev. Samuvel Mateer, of the London Missionary Society, in his book ‘Native Life in Travancore’, published in the year 1883, refers to Ayyappan as a ‘hunting deity’ whose ‘Chief shrine is in Savarimala, a hill among the Travancore Ghats…’.

The reference to Ayyappan and his one-time chief priest Talanani appear in Chapter VI which deals with the ‘Hill Tribes’ of Travancore, who were ‘tribes of wild, but inoffensive mountaineers, occupying the higher hills and the mountains of Travancore, finding a rather precarious living by migratory agriculture, hunting, and the spontaneous products of the forests…’

Samuel Mateer’s portrayal of Talanani, ‘a priest or oracle-revealer of the hunting deity Ayappan’ is intriguing, and appears in pages 75 to 78 of the book. Talanani, according to ‘Rev. W. J. Richards, of Cottayam’, was apparently a Mala Arayan who ‘belonged to the Hill Arayan village of Erumapara (the rock of the she-buffalo), some eight or nine (miles) from Melkavu’.

Extracts from the book :

‘…..Rev. W. J. Richards, of Cottayam, has favoured me with the following history, which throws much light upon this curious superstition:—

“Talanani was a priest or oracle-revealer of the hunting deity, Ayappan, whose chief shrine is in Savarimala, a hill among the Travancore Ghats. The duty of Talanani was to deck himself out, as already described in this book, in his sword, bangles, beads, &c., and highly frenzied with excitement and strong drink, dance in a convulsive horrid fashion before his idols, and reveal in unearthly shrieks what the god had decreed on any particular matter. He belonged to the Hill Arayan village of Erumapara (the rock of the she-buffalo), some eight or nine from Melkavu, and was most devoted to his idolatry, and rather remarkable in his peculiar way of showing his zeal. When the pilgrims from his village used to go to Savarimala— a pilgrimage which is always, for fear of the tigers and other wild beasts, performed in companies of forty or fifty—our hero would give out that he was not going, and yet when they reached the shrine of their devotions, there before them was the sorcerer, so that he was both famous among his fellows and favoured of the gods. Now, while things were in this way, Talanani was killed by the neighbouring Chogans during one of his drunken bouts, and the murderers, burying his body in the depths of the jungle, thought that their crime would never be found out; but the tigers—Ayappan’s dogs—in respect to so true a friend of their master, scratched open the grave, and, removing the corpse, laid it on the ground. The wild elephants found the body, and reverently took it where friends might discover it, and a plague of small-pox having attacked the Chogans, another oracle declared it was sent by Sastavu (the Travancore hill boundary god, called also Chattan or Sattan) in anger at the crime that had been committed; and that the evil would not abate until the murderers made an image of the dead priest and worshipped it. This they did, placing it in a grave, and in a little temple no bigger than a small dog kennel. The image itself is about four inches high, of bronze. The heir of Talanani became priest and beneficiary of the new shrine, which was rich in offerings of arrack, parched rice, and meat vowed by the Arayans when they sallied out on hunting expeditions. All the descendants of Talanani are Christians, the results of the Rev. Henry Baker’s work. The last heir who was in possession of the idol, sword, bangle, beads, and wand of the sorcerer, handed them over to the Rev. W. J. Richards in 1881 , when he had charge for a time of Melkavu…..”

– Joy Kallivayalil.

Rev. Samuel Mateer’s book ‘Native Life in Travancore’, published in 1883, can be accessed here: https://archive.org/details/nativelifeintrav00samu/mode/1up